Aping the Beauty’s Frown (1)

- EdTinker

- Sep 10, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 10, 2021

Teaching Critical Thinking in Chinese Schools

Preface

I began to teach a school-based course Critical Thinking and Writing this year. In the first class, several students asked me to clarify the term of Critical Thinking. Every one seems to talk about critical thinking, but they found no uniform and clear common understanding of it. Less can they grasp the essence of critical thinking in the purpose of developing it. I think they asked a good question, however, my answer to their question could disappoint them if not confuse them further. There is no unanimously agreed definition of critical thinking!

The discussion with my students in class reminded me of one article that I wrote when I took an Educational Philosophy course at the University of Toronto. It was written nine years ago, but some discussion in it is still relevant. Especially, I talked about Chinese IB teachers' understanding of critical thinking in the article. I am going to recommend my students to read it as a course reading. The article is long, so I break it up into three sections.

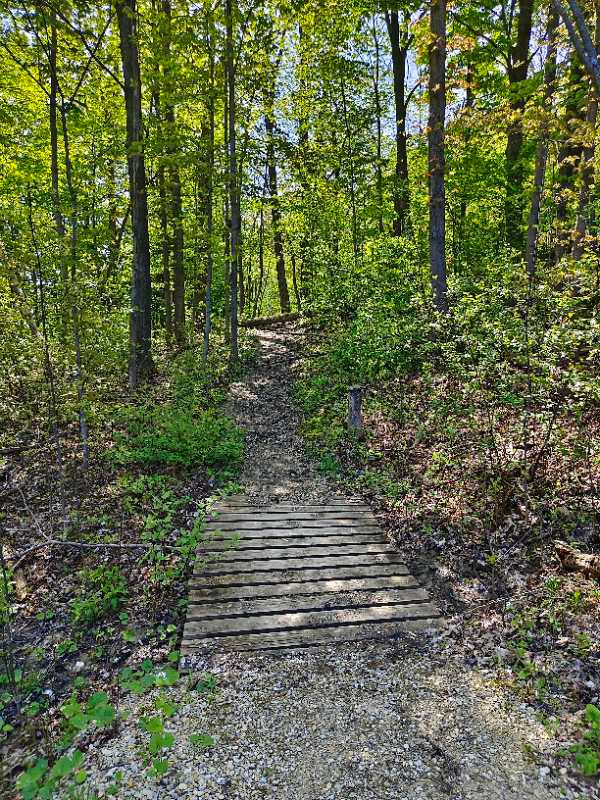

Photo taken in ECNUAS HS on Sep. 10, 2021

The Story of Aping the Beauty’s Frown (Dongshi Xiao Pin)

There was a beauty in the State of Yue named Xishi in the Spring and Autumn Period of ancient China. Xishi often suffered from chest pains, and so she would often walk around with her brows knitted. There was a plain-looking girl in the village called Dongshi who admired Xishi’s beauty. Striving to emulate Xishi, Dongshi imitated knitting her brows. She thought that this made her elegant, but, in fact, it only made her awkward. Later, this idiom came to be used to indicate improper imitation that produces the reverse effect (Cultural China, 2012).

Critical Thinking (CT) and me

When the notion of Critical Thinking occurred to me first time ten years ago when I started to learn about the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme (IBDP), I didn’t comprehend the exactly meaning of this term CT. More precisely, I should say that my understanding, like other Chinese, was not on the same page as the western people perceive CT. For the people who grow up in western culture, CT is presumably fostered throughout their life from early ages to post-secondary education. CT is culturally recognized and it evolves inherently in the western society, no matter how well CT teaching has actually achieved in schools and how different people’s opinions about CT possibly are. However, as a Chinese teacher who grew up and was educated in China, I had no idea about the notion of CT before I started to work in IB. What I did know was that since I served in IB I would have to accept and embrace this Beauty designated by the IB authority. I didn’t think too much about whether or not it was a real Beauty as my intrinsic cultural habit of “respecting authority” prevented me thinking in that way. What I pondered more was how to learn to criticize other’s opinions because I was inevitably influenced by the Chinese version of CT — Pi Pan, the misleading Chinese translation of the English word “Critical” as later I shall show. When I had to teach and guide students on CT, I felt I was just superficially imitating some basic techniques instructed by the IBO. Like the above the famous Chinese proverb depicts, I was just “Aping the Beauty’s Frown”. As I have been teaching, and learning too, in IB for a longer time, now I realize it ought to be the time to correct my understanding of CT and to think critically about CT in the Chinese context in a way that could benefit other Chinese people who might have shared or will experience the same struggles on this matter as I did. I shall start with exploring CT in the western culture.

CT in the Western Culture

The importance of CT for education is not new to western culture. Etymologically, the word “critical” has two ancient Greek roots: “kriticos” (meaning discerning judgment) and “criterion” (meaning standards) (NCECT, 2012). CT can also be traced back to Socrates’ ideas about education. Socrates’ believed that CT is central to education and cultivating effective thinkers is the goal of educational systems (Bailin, 2005).

However, the debates on the conception of CT and on how to effectively teaching CT have never ceased in the western academia. Based on a large scale study, Paul, R. et al (1995) found that this well accepted, however controversial, notion of CT was by no means satisfactory when it was applied by educators.

Most faculty have not carefully thought through any concept of critical thinking, have no sense of intellectual standards they can put into words, and are, therefore, by any reasonable interpretation, in no position to foster critical thinking in their own students or to help them to foster it in their future students-except to inculcate into their students the same vague views that they have.

Bailin et al (1999) duly pointed out that CT is a normative term and CT should be conceptualized in terms of “intellectual resources”, including background knowledge, knowledge of CT standards, possession of critical concepts, knowledge of strategies or heuristics useful in thinking critically, and certain habits of mind. For teaching CT, Bailin et al (1999) believed that this “intellectual resources” approach can be helpful for “deciding questions about curriculum and instruction” , and that CT is best to be taught in contexts rather than “teaching isolated abilities and dispositions”. Siegel (2001) defined that CT has two components: “the skills of reason assessment” ; “the attitude, disposition, habits of mind and character of traits”. And he argued that education for CT should foster both of the two components. Egege and Kutieleh (2004) were inclined to teach CT in separate university transition programs instead. To teach foreign students, they argued that the well-accepted concept of CT in the western universities is not universally valued across different cultures and therefore CT must be viewed as a culture concept, and that this cultural approach should be incorporated into these transition programs in order to avoid either culturally insulting “assimilation” or “deficit” approach of teaching CT. The National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking (NCECT) published its widely-cited definition of CT, which showed that CT consists of a process of mental activities and it can be taught and its intellectual value is universal:

Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness. (Scriven and Paul, 1987)

Mulnix (2010) claimed that CT is the same as thinking rationally or reasoning well and argued that CT can be fundamentally and simply defined as “the ability to grasp inferential connections”. Hence, he suggested the approach of “extensive use of argument mapping” in teaching CT to increase the ability of grasping “inferential connections” between statements.

In summary, it is clear that CT is a broadly embraced Beauty of the western culture, which is the most influential strand of the human culture at the present time. It is also clear that CT is important to learning, living and even human civilization advancement in modern society (c.f. Siegel, 2001; Pinto and Portelli, 2005). However, because of its normative nature and culturally developed features, no matter how hard scholars try to interpret CT, the controversy and vagueness about CT could be perennial. When CT comes to teachers’ teaching practices, no conception seems to be universally useful and teachers in the field seem to be just acting by following their own personal understandings. Probably CT teaching has to rely on teachers’ discretion and hopefully they are guiding students’ CT in one way or another. Nonetheless, for those who hold vague or even erroneous concepts of CT, their teaching under the name of CT could be problematic. Before I investigate the case of a Chinese IB school, I shall look into IBO’s requirements on CT first.

コメント